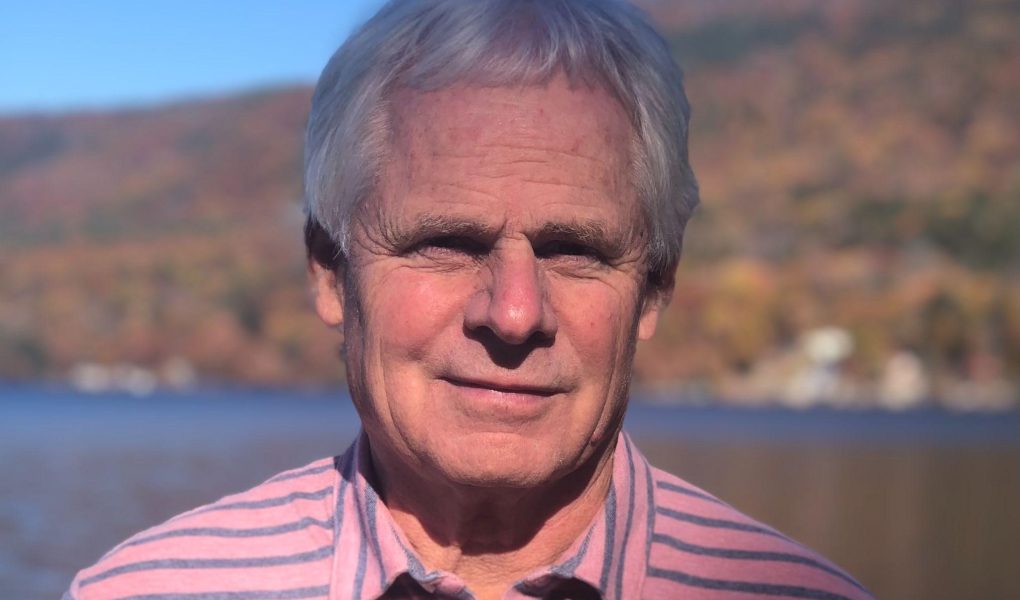

Gary Wright is a retired college hockey head coach of thirty-two years at American International College (AIC) in Springfield, MA. Coach Wright recently published his memoir, Striding Rough Ice: Coaching College Hockey and Growing Up in the Game. He details his early years learning to play hockey on the frozen pond, suiting up to play for his hockey coach father at Proctor Academy, persevering through adversity to play NCAA hockey for the University of Vermont, entering the coaching profession at the high school ranks before moving to the college level as an assistant coach at the University of Maine, and all the way through his long career as the head hockey coach at AIC.

Kevin LoGiudice: During your playing days, you never gave up and persevered through adversity to finally play in a Catamount sweater at the University of Vermont. What advice do you have for young people today who find themselves at a similar crossroads in life?

Gary Wright: Hockey was a big part of my life and I grew up with my father being a coach, so playing the game in college was important to me. Recruiting wasn’t quite as sophisticated back then, so I took a little bit of a risk going to Vermont where I wasn’t considered a recruit. When I was cut from the team as a freshman, I got a break as a sophomore when they decided to have a JV team. I was very fortunate that opportunities came to me in different ways and I was able to work my way onto the NCAA team. I think stick-to-itiveness is an important quality to have, but when you’re looking at colleges or extending your sports career, you also need to have a realistic view of your own ability level. There’s the famous quote by Winston Churchill I mentioned in my book about never giving up. That is the best advice I can pass along. Having that type of mindset is a really important quality in life, no matter our pursuits.

What qualities did you look for in players you recruited and assistant coaches you hired?

I tried to look at the person as well as the player. They didn’t necessarily have to be great students, but I certainly wanted players that valued education and wanted to graduate with their degree. Work ethic, character, coachability, being a good teammate — I think those are all qualities I looked for in players. One of our approaches was to vet players by not just talking to their previous coach, but to go back and speak to their coaches before that. We had good luck with assistant coaches too. We weren’t a big profile program at AIC, but we attracted some pretty good assistants. A number of them have gone on to do great things. We always had a part-time graduate assistant position — at one time that is all we had. The downside was that they rarely had any previous coaching experience, could only stay for two years, and then just as they gained experience, they’re out the door. On the other hand, because it was a two year position and we were getting younger guys that weren’t necessarily well known, we were able to hire some coaches that maybe wouldn’t have gotten an interview at other places, but had lots of potential. Next thing you know, they join our program, do a really great job, and make a career out of college coaching. I always strived to get people who love the game. If someone doesn’t love it or it’s not what they want to do passionately, they’re probably not going to give you the same kind of performance as someone else who might be a little less talented, but wants it more.

In the 90’s you published a book, Pass the Biscuit: Spirited Practices for Youth Hockey Coaches and Players. What is your favorite hockey drill?

I don’t know if I have any one favorite drill, I would have to think about it. One of the things I talked about in Pass the Biscuit — it sounds more like a cooking book — was small games and drills that make the players think for themselves. I grew up playing outdoors and now that hockey is more structured, indoors, and in arenas, there’s a nod back to that era with an effort to duplicate drills and practice components that exemplify the virtues of playing outdoors. I was a little bit of a drill junkie and it was really one of my favorite parts of the game. Not just my own drills, but as former Yale Bulldogs Coach Tim Taylor said, “we’re all drill pirates.” You can tell the popularity of some drills just by how the players react when you announce it out on the ice. If they’re going 100 miles per hour all fired up, it says a lot about the component of fun as a motivator.

With a lifetime in the hockey world, how has the sport changed from playing on the ponds of your younger years to the large indoor rinks of today? How do you see the game evolving in the future?

That hasn’t necessarily been something that’s on my mind because I haven’t coached for a few years. I watch a fair amount of hockey and the game really does advance in so many ways, whether it’s scientifically or tactically. Those little things in terms of health and strength and conditioning. It seems like every decade there’s huge jumps in these areas. Hockey has acquired an awful lot of structure offensively and defensively. There’s some concern whether “too much analysis is paralysis.” Are there enough areas of the game left for the players to think for themselves?

What lessons did you learn from coaching that would be valuable in leadership?

One of the things I found especially appealing about college hockey was that the sport was played and encompassed within an educational setting. Not only that I was coaching a sport I love, but that it exists within the confines of an educational institution. A vibrant campus with lots of young people was a big attraction for me when I coached. I have great respect for professional hockey, but there’s a lot to be said for people who are educators overseeing college athletics. I think in a lot of respects the rink is an extension of the classroom. We are educators as coaches, and athletes are given the opportunity to play at the next level, but they’re also walking out with a degree. I tried to take a real interest in my players, instill discipline, provide real life lessons, and make sure that I was never afraid to lose. If it meant I had to sit a great player for whatever infraction, I would just do it because no message is going to get through better to a player than taking away ice time.

How did you get to know all of the hockey players on your team each season?

One of the things players are most interested in from their coach is how much you care about them. I coached golf for five years at AIC and another coach said to me, “You might get to know your golfers a little bit better than your hockey players.” This was because there’s only ten golfers on the team and only about five of them traveled to compete compared to a roster of thirty hockey players. Getting to know your players as individual people should not only be important if you’re going to be their coach, but you should also just want to. I’m no expert on this stuff, but I think player-coach meetings have real value. These meetings should not be just to talk about somebody’s ice time, but to make a point to really reach out and get to know your players beyond the rink. Assistant coaches can have even more access to players than head coaches; they can talk to them about things which really help them and help our team at the same time. So it’s a good thing to hire a coaching staff who are people persons. Beyond that, you have to enjoy your players and want to be around them. If you’re not winning or don’t have as strong a team as you’d like, players are probably going to listen to you during those difficult times instead of turning south if they feel you really care about them as people.

During difficult seasons, how did you continue to keep your teams together?

One of the most important qualities in athletics — or any part of life — is to endure defeat without losing hope. First, there can’t be any quit in the coach. That means even the little things like making sure skates are sharpened, the bulletin board has fresh material, practice has upbeat drills, the atmosphere is fun, and there’s good communication. It is important to keep doing things that are going to make you better. I think you have to maintain discipline because if there is ever going to be a time when people will take advantage, it will be during those difficult times. As a coach you have to show your team every day that there’s another opportunity to win a hockey game coming up. If you’re coaching through adversity, such as a losing season, you have to realize that ironically you must do your best coaching job. For example, in years when we had a lofty power play percentage, we probably spent about a third of the time practicing it as opposed to other seasons when we were struggling. You may get a lot more credit when things are going well, but you need to be at your best when you are facing adversity. Hopefully, you’ve hired good assistants and recruited character and chemistry players who will help you get through the tough times. Besides hockey, we’ll need to deal with loss a lot in life: jobs, our fondest dreams, our spouses, our parents. Loss and adversity are very much a part of life. To be successful, you’ve got to be able to work through those difficult times with a positive attitude and incredible fortitude.

How did it feel to look through all of your old notes, score sheets, trophies, etc. compiled through your life in hockey when writing your book?

It was a fascinating experience for me. When I was writing, I almost felt at times like I was right back in the moment. I interviewed a lot of former players and the interesting thing is — you talk about events going back 20 or 30 years — sometimes you can’t get people to agree on how things happened. I did save a lot of old press guides, newspaper clippings, and the like. My last few years at AIC, my mother always used to tell me to write stuff down, and if I were to do it over again, I would have taken more notes. She published over 20 books in her life, so she encouraged me to write the book. As I was writing, she reviewed it and gave a few grammatical suggestions that were important, but most of it was encouragement. So she came into my hockey world and I entered her writing world.

What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

I wrote the book in some sense to celebrate the greatness of college hockey, coaching, and the people involved. I hope readers will get a real appreciation for those things and there may be some experiences of mine they can bring to their own lives. It’s really remarkable when I look back at some of the coaches I had, how caring and dedicated they were, and how beneficial they were to my life. So much of the game is about the people. We are very much a product of those who have influenced us. There’s a lot of “how to” or “X and O” books, but not quite as many about the people in the game. I hope to honor all those incredible people that touched me along the way.

Was it difficult for you to reveal in your book that your coaching career did not come to an end by your own choice?

Yes, it was difficult, but necessary. Actually, I considered whether or not I was going to discuss this subject, even before I started writing. If I weren’t writing a book, it would have been easier and less awkward to leave my resignation as a personal choice but unfortunately that’s not the case. And, if you’re going to write a memoir, it kind of needs to be in there if it happened, right? I think so. I was around 63 at the time my coaching career ended and it probably would have hit me a lot harder and felt more catastrophic if I were younger. I decided at that point that I wasn’t going to be in hockey that much longer either way, so I accepted my fate and moved on to the next chapter.

After living so much of your life in Springfield, MA, why did you retire back in Vermont? How do you spend your days now?

All of my family are here in the area and I always planned to go back home to Vermont. Springfield, MA was very different from the environment that I was brought up in, but I grew to appreciate the city, the college, and the people. Working on the book when I moved back to Vermont was a great transition period because it took four and a half years. I’ve stayed pretty close to hockey in general by watching a lot of games. Now I play a lot of golf, do quite a bit of reading, and hike with my dog, Hobey. Initially, I took Hobey for walks and hikes because I thought it was good for him, but I’ve realized it’s just as beneficial to me so we go somewhere almost every day — sometimes a full-scale hike, other times a brisk walk in the woods.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.