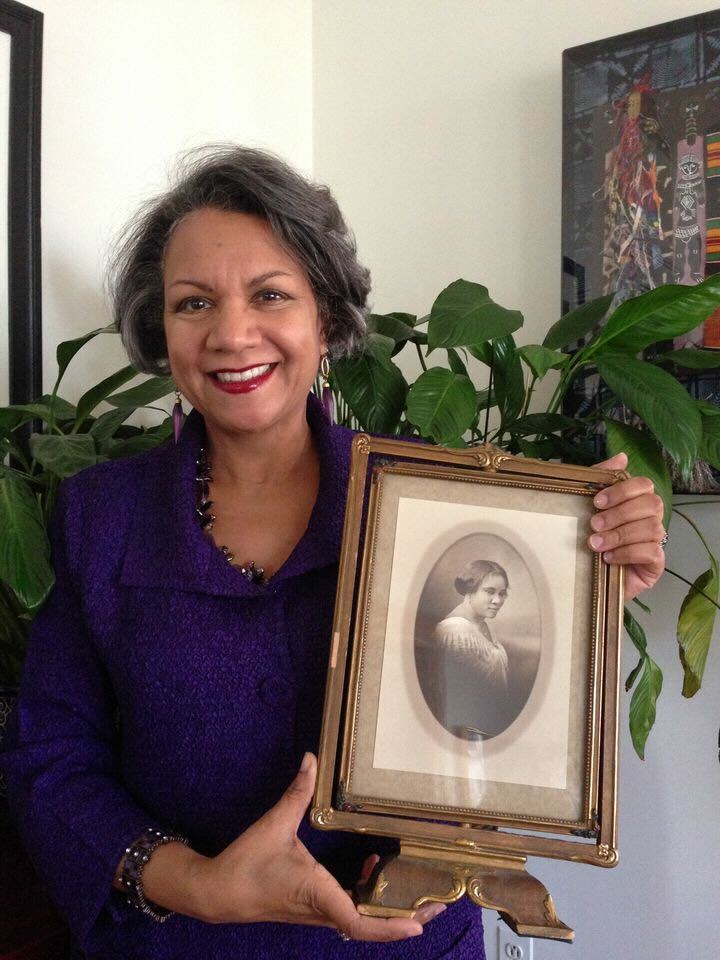

A’Lelia Bundles is an esteemed American journalist, author, and public speaker. She is best known for her extensive work chronicling the life and legacy of her great-great-grandmother, Madam C.J. Walker, the first woman millionaire in United State’s history for her natural hair care company tailored for Black women. Bundles has authored several critically acclaimed books, including the biography “On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker.”

A graduate of Harvard College and Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Bundles has had a distinguished career in broadcasting, including producer roles at NBC News and ABC News. Bundles founded the Madam Walker Family Archives and later collaborated on producing MADAM, the hair care line inspired by her great-great-grandmother’s original hair care recipes. Bundles serves on the boards of the National Archives Foundation and the Madam Walker Legacy Center and through her writing, speaking, and advocacy, she continues to inspire and educate us about the rich history and contributions of African American women in business and society.

In this interview, we discuss why she finds it so meaningful to explore one’s family history.

Before reading, please check out my video, Natural Hair: The History and The Joy In The Movement. This video essay explores the life and legacy of Madam C.J. Walker and her pioneering hair care company, which paved the way for today’s natural hair movement. This video premiered this year at the Brown Film Festival in New York City and Beverly Hills.

****

Paige Censale: So I want to start off by saying happy early birthday, that’s not bad luck to say that in the US – are you going anywhere?

A’Lelia Bundles: I’m really just trying to finish this final chapter that I have… I’m hoping by the time my birthday gets here at the end of the week, that will be my birthday present to myself – editing this chapter.

Can you tell me more about this book you are finishing?

This is a new biography on Madame Walker’s daughter, A’Lelia Walker – my namesake – and her life in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance – her parties, her travels. People who have done her story, have not really done her justice and have kind of caricatured her. This is my effort to really tell her story in full.

Is there something more than just your great-great grandmother’s hair business that you would want to unearth about her?

Hair is just kind of the starting point, and the hair care products became a means to an end that was much broader. Madam C.J. Walker realized that women absolutely needed haircare products that were tailored to them, but they really needed education and financial independence.

I love expanding that story about her, talking about her as an educator, as a political activist, as a patron of the arts, and as somebody who helped to create generational wealth for Black women and Black families. I also loved discovering what a political radical she was. In Philadelphia in 1917, she held one of the first conventions of American women entrepreneurs and she gave prizes. Not just to the women who sold the most products, but to the women who contributed the most to charity. She said to them, ‘Your first duty is to humanity. I want others to look at us and realize that we care not just about ourselves, but about others.’ And at the end of the convention, the women sent a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

Did your passion for putting together your family’s history start at Columbia, or even before then?

I totally resisted it in high school. My senior year in high school in the spring of 1970, we had to lobby for a Black history course, a humanities course, because I was in a predominantly White school. After King’s assassination, a group of us said we really want a Black history course and we got this course and I really ended up writing about A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance because at that point, I was older and really not interested in Madam Walker – she was too complicated. I don’t remember whether I came up with this topic on my own or if my mother first suggested it. But she [my mother] went up into the attic and pulled out a box that had the original invitation and menu from The Dark Tower, and some books signed by Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. So A’Lelia Walker was kind of my entree to doing family history. But then…Phyl Garland, who was my advisor for my master’s paper at Columbia, recognized my name as A’Lelia and realized that I had a connection to Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker and said, ‘this is what you are going to write about.’ That was what really validated it for me and put me on this path.

What did you originally turn in for that year-long paper at Columbia?

I don’t know, probably a 30 page paper or something. The research that I had done on Madam Walker was pretty preliminary. I mean, actually my mother died when I was in graduate school, she died that year. So I talked with her, I talked with my grandfather, I had a few letters here and there. She was mentioned in a few books, and I interviewed a woman who had been her secretary since 1914. So I wrote what I had at that point.

Fast forward another few years, Alex Haley came to us and said he wanted to do a mini series about Madam Walker. We had dinner in New York, and he said he was going to hire a bunch of researchers and blitz this story. And I said, ‘Excuse me, Mr. Haley, I wrote my master’s paper about Madam Walker, maybe I’m the person who should do the research.’ So I took a leave of absence from NBC, where I was working in the Atlanta Bureau, and spent a summer in New York interviewing the survivors, the people who had known A’Lelia Walker during the Harlem Renaissance. We were really fortunate that the secretary had saved Madam Walker’s letters and business records. So literally, at this point, I now had 40,000 documents that were digitized…all of those letters I used as the foundation for my research.

Did you have a team to help with the research, or was it just you?

I mean, there was a desk assistant at NBC who photocopied some things for me, but it was basically me. I was the one interviewing people, I traveled around to a dozen cities, went into historical societies and courthouses and manuscript collections, and it was really a labor of love to be able to make that discovery.

How did you decide where to hold all of Madam Walker’s archives? Did you keep some archives just for yourself?

The Walker Company papers are housed at the Indiana Historical Society; 40,000 of them have been digitized. Since the Walker company was based in Indianapolis, the Historical Society sort of recruited the estate in the 80’s and so the bulk of the Walker company papers are there. But there are also lots of things that I have inherited. In fact, my house is now a little overcrowded. One of the goals of finishing this book is to clean out all of this stuff that’s here. I have one room next to me that is filled with milk crates, and thousands of manila folders with chronologies and tons of things. Writing a biography is a really long process.

In your next book, you are looking to change the narrative around A’Lelia Walker, Madam Walker’s daughter, who everybody kind of characterizes as the one who spent all her mom’s money and was all over the place. So what is your take away on that? Can no one person be defined to just a single sentence?

We’re living in a bumper sticker kind of world, where we just want people to be whatever the headline is. I think that the ancestors deserve more than to be put into a little box. People are complicated. So, how do you really look at a person in full? I mean, these kinds of stories take a long time to listen to and read about. I don’t think a lot of people want to do that…I hope that there will be people, and I do have a lot of friends who are historians, who are professors, who can’t wait to teach this book.

How did you find the portrayal of your great-great-grandmother in the Netflix series, “Self Made”?

The Netflix series was a lesson learned. Warner Brothers was really the producer, Netflix was just the platform where it aired. I was really supposed to be much more involved in the shaping of the narrative: they hired a writer who did not really have a lot of experience, and they actively excluded me from the process until it was too late to really make any changes. I would work with Netflix again; it was not Netflix’s fault. It was the showrunners and the head writer who decided they wanted to tell a story that was really different from the story that I thought should be told.

That makes me think about the whole premise of American Fiction, and how Hollywood and the depiction of Black peoples’ stories are made into a flat trope. Unfortunately, “Self Made” fell into that when it could’ve been so much better.

Yeah, it was quite sensationalized. It was made into a catfight between two women. They sort of introduced colorism as a conflict, which it wasn’t. They made up a girlfriend for A’Lelia Walker, when her real conflict was with her mother…I mean, it was just like a whole lot of stereotypes. But Octavia Spencer was sort of the best part of it, because even with the script that she had worked with, she still, I thought, did Madam Walker justice in terms of portraying her.

Lots of people worked really hard, so I don’t want to trash everything about it, but I just was really disappointed. I was really hoping for Hidden Figures and I feel like it veered toward Real Housewives of Atlanta…When writing about historical figures, especially women and people of color who have rarely been portrayed accurately in Hollywood, it’s crucial to avoid falling back on stereotypes and clichés. These portrayals often lack depth and thoughtful consideration. As a result, many people may mistakenly believe that the story being told is an accurate representation of Madam Walker’s life.

But I thought [American Fiction] was great. In fact, I just finished reading Percival Everett’s new book, and I’m going to hear him speak on Friday. And yes, Hollywood, you gotta make things dramatic. But there are directors and writers and producers who just have a different mindset and have more integrity about how to tell our stories. Like you do not entirely make up a character who is a pimp – like that person did not exist in Madame Walker’s life.

And the script made me cringe, because the first version they sent me, Madam Walker, and Annie Malone…they were calling each other the ‘N’ word and the ‘B’ word. Like, trying to, I guess, make it hip and contemporary. But Black women in the early 20th century, it’s not like they couldn’t throw shade, it was just not in this way. It was just so off.

That’s too bad, but it sounds like you were much more involved in the Madam Walker hair line that came out?

Yes, it was kind of a partnership between Walmart and Sundial Brands at Unilever. And it was really because a sister who was an executive at Walmart really wanted to be able to introduce this line.

They have this wonderful team of young creatives. We met on Zoom because it was still during the pandemic, and they gave me their concepts of how they wanted to brand it, and what partnering they wanted to do, and so there was the packaging, they sent me the fragrance – it really was a great collaboration.

Can you tell me about your career as a journalist? How did you get started, where did you start?

When I was in high school, I wrote for a teen supplement with the local daily newspaper. There were representatives from each school. One of the perks of that was that you got to spend a day at the newspapers, shadowing reporters. But as a girl, they sent me to the women’s section, because that’s where women journalists were. Women were not writing political stories and the hard news. So for that period of time, that was the path that it looked like women should follow. By the time I got to college, I had an internship at Newsweek one summer, and it happened to have been the summer of the Watergate hearings. And the doors were opening up for women and for people of color. By then, I was starting to see myself as a journalist who did not have to be consigned to the women’s pages.

Once I finished at Columbia, I was hired by NBC in what was called a management training program. This program came about partly because some women had sued local stations and weekly magazines over disparities in the workforce. When young women were hired at that time, they were typically employed as researchers and secretaries. In contrast, young men were hired as desk assistants and assistant producers. Ten years later, the women would still be secretaries and researchers, while the men had become producers, senior producers, and executive producers. So I was really fortunate to come along when those doors were starting to open.

What was your career like once you started working for NBC and ABC?

As a producer you gather the photos, and, you know, maybe help with some of the interviews, but it was really the correspondent who would write the scripts, when I worked for the magazine shows. I did some of the writing, but my job was not primarily as a writer. I was just doing writing on the side. When I started in 1991, I actually wrote a young adult biography of Madam Walker. So then I had my first book, but it was a young adult book. Then I got the contract to write On Her Own Ground.

You worked in production at NBC and ABC news, but did you ever want to be in front of the camera?

I knew I could be in front of the camera, but this was an issue of hair. When I was hired in this management training program, I mean, that role was behind the scenes; the idea was that there weren’t enough women and people of color in management. So that was a good track to be on. Because, you know, that’s where the decisions are made around the editorial page and table. However, I knew that in order to be on air, I would have to go to a small market and sort of work my way up. I didn’t really want to do that. But I also had a big afro at that point, and I did not want somebody telling me how I could wear my hair. And so that was it. I stayed on that producer path rather than saying, ‘I’m going to get off this path and go become a reporter.’

Honestly, this issue of showing your natural hair on television is still a real thing today, wouldn’t you say?

My last job at ABC was Director of Talent Development, so I was working with new correspondents when they first arrived. I helped them with, you know, clothes, and hair, and presentation and narration and all of those things, and it was definitely a milestone when a woman with natural hair appeared on ABC air: Michel Martin, who was at Nightline. Michel had established herself as a solid reporter, I think at the Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. And Michel has a really strong personality, and she’s like, ‘I’m not changing my hair!’ And that was a big deal, because before that, you know, natural hair [elicited responses from employers like], ‘this person doesn’t really have the right look.’

Jackie Trescott at the Washington Post or Charlayne Hunter-Gault, who was at the NewsHour on PBS, they had natural hair, but that was, you know, radio, newspapers, and PBS. Women on network television news [with natural hair]– that took a long time…

So it’s been interesting to me to see that evolution. I would say it’s still an issue at a lot of local stations, especially outside of major markets, because there are a lot of racists who call the stations and comment about it. Like, they don’t want to see that person with that hair. But one thing I have noticed, particularly during the last decade, is that a lot of women, Black women, who are attorneys, who are really good at what they do, a lot of them have natural hair. And their hair comes with their brains. And so they’re like, ‘if you want my brain, here’s my hair.’ And Justice Jackson is a total example of, you know, here’s my natural hair!

You said in another interview that your father was nervous about you wearing an afro? Could you tell me more about that?

That was in the 50s and 60s, and by then the Walker company really was no longer a major leader. As companies like Johnson products, SoftSheen, chemical hair straighteners, those became much more popular. My dad became president of Summit Laboratories, which was one of the companies that made chemical hair straighteners.

So when I was growing up…I wanted an afro and my dad was totally against it because his company made chemical hair straighteners. But my mom still was at the Walker company and she took me to the Walker beauty school where the students rolled my hair up on permanent wave rods, because there was still perm in there. So it was kind of a battle in my household. And this was happening in households across America, where parents just thought if you have an afro, you’ll never get a job and your life will be over. But for my father it was particular because he was seeing the competition from other companies.

Why do you find it so important for the next generation to learn about the people who came before them?

My mom died when I was in graduate school. I was in my 20s…[Because of that] I do feel like it’s important that I tell these stories, because it’s what keeps them alive. You know, my house, and the storage room that I rent are the repositories of everybody in my mother’s family. I mean, I’m the one who cleans up the houses and gets the papers and tries to preserve them. So what I know is only because they save these things.

The stories of our ancestors – it’s a source of pride for me to see somebody else know that their great-great-grandfather, whatever the story may be, was a teacher, was a farmer, was an attorney. It helps you understand who you are.

So I am an opponent of these people who want to ban books. When I see somebody trying to rewrite history or sanitize history, they really want us to not feel that we are important. It is that basic. So I’m always encouraging people to save those things.

You know, now every young person has a smartphone, they can turn on their camera and interview their grandparents. And if every time an eight-year-old, ten-year old, sees their grandfather, their grandmother, and they take out their phone and do three minutes worth of an interview, over time, you’ve got hours of questions that this child asks, and that helps the child go back and understand things.

When somebody dies, then the impulse is like, ‘Let’s just throw everything out. There’s all this mess in Grandma’s house.’ But as various members of my family have died, I have gone through every box and every piece of paper. And yes, most of it you do throw out, because you don’t need it. It’s old newspapers or, in my grandfather’s house, old racetrack tickets. But in the midst of all of that there are gems, there are diplomas, birth certificates, love letters between great-grandparents. Those things tell a family’s history and a family’s story. And whether you know it or not, you are the accumulation. So it is good to know what those ancestors were doing, the sacrifices they were making, the dreams they had for you, and the dreams they had for themselves.

What are you doing now to save your own story?

In some ways, I’m talking about myself all the time. So I mean, my story is out there, but I don’t have any desire to do a memoir. I guess I have more of a desire to be the person who facilitates other people telling their stories. Some of that is being a journalist for a long time, I was telling other people’s stories. I’m interested in other people’s stories. I’m interested in other people and empowering other people to tell their stories.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.